Alis / Filliol – Check your Totem

Press-release

Pinksummer: Let’s start from the title of your show at pinksummer, “Check your Totem”. James Frazer asserts that “the totem it is nothing but a closet, where a man keeps his own life”, some sort of safe for the soul, often secret. It seems, then, that, among not too dogmatic totemic societies (savage? primitive?), one can have as many souls as needed, one for himself, one for the clan and so on, and that souls can even be exchanged. This happens most of the times during the initiation ceremonies concerning death and resurrection, but it can occurs also while hunting, when someone exchanges his soul with his totem’s one.

In his book Totem and Taboo, Sigmund Freud assimilates, or rather compares, totemic societies’ taboos to the ambivalence of the removal process of some neurotic patients.

Actually, while reading your title, we have been thinking a little at Roberto Cuoghi. Would you tell us about that title please?

Alis/Filliol: “Check your totem” is an idiom that became part of slang in U.S.A. in 2010, after the release of the movie “Inception” from which it was taken. That sci-fi film is about a world, where the main characters can enter the dreams of those from whom they mean to embezzle some otherwise unattainable information. Each of them possesses a kind of amulet, called “Totem”; an object endowed with a particularity, known only to the one who carry it with him, that let its owner understand which dream he is in. If he is in his dream or in someone else’s. It is an object that can define in which reality the protagonist is living.

In the American slang, that expression is used in a sarcastic sense, for example, to address a friend spot in a moment of confusion, caused by what surrounds him or her.

Beyond its cinematographic origin, we were surprised by the fact that that idiom has become part of the common language, joining far ancestral references to the contemporary everyday life experience.

Totem itself embeds a variety of lost and present diverse qualities, that seems to escape any attempt of total understanding, as if the origin of the humanity came from the same ideal source, where the totem is a pivoting figure.

More than the attempt to explain its anthropological, psychological or philosophical origin, we are interested in the perception of the physical presence of the totem, its subtracted image.

The illusion as the only possibility of actualizing its substance.

P: You call yourself sculptors. Considering how Ejzenstejn uses sculpture in the movie “October”, Rosalind Krauss claims that sculpture, like every art, and – we would add – more than any other art, it is basically ideological.

What is your attitude towards sculpture in that sense? Also, isn’t an artist duo a paradox for such an absolute and self-accomplished art, projecting images into the three dimensions?

Alis/Filliol: The good thing about a movie featuring a sculpture is that you can look at that sculpture through the eyes of the director. Actually is he who has chosen the sculpture as a subject, especially if that was made purposely for the movie. Shooting just a part of it despite the whole unit, rather than framing the entire sculpture from a given angle, including space and people surrounding it, is a necessarily meaningful choice, totally up to the author.

For us, being sculptors, immanence is fundamental. It is something that film as a medium tends to conceal in favor of the immersive vision of the demiurgic director’s space/dream .

That is the articulation concerning the relationship between body, space and limit. Sculpture is a physical limit that places itself against the motion of a body like an obstacle. The appeal of this limit, of this boundary, is based on the fact that it cannot be described as a line but as a centre. Being a centre, it can be encircled. What mainly distinguishes sculpture as a nucleus, as a centre – and what fascinates us – is its impenetrability. The gaze bounces on the sculpture and goes back to the body, binding it down to the present.

The encounter with the sculpture is not only that one with an alien body, that reflects our unicity through contrast. What can be observed is the paroxysmal solidification happening between two opposite forms of mobility: the still one of the object-sculpture’s dense matter and the hyper-mobile one of the unstable system that has formed it.

Our fellowship is a small social body, formed by two individuals, that needs to be able to become solid, by reasserting and replying itself again and again, just like bigger social bodies do restless.

P: Speaking about totemism and the ideological nature of sculpture, it happens – it happened recently in Syria and Libya – that, as soon as a dictator is dismissed, his effigy is immediately and violently removed from public squares by the people. The cathartic fury with which people put into effect such a “deposition” has always let us think to some sort of apotropaic memory of deicide performed by primitive people. By removing the sculpture, they remove the evil and the suffering that has been transferred to it. Anthropologically, as a matter of fact, sculpture tends to let the borders between physical and mental, material and spiritual, disappear. This happens simply because sculpture, at least when becomes a monument, signifies toward its outside, within a public space and audience? When can one sculpture be defined a monument?

A.F:From our point of view, every sign is an object, like, for example, a word. Before being expressed, every thought is lively linked and confused with the mental life itself. It is like if, instead of enjoying autonomy, it would enjoyed the dependency of the small living chaos, to which it is connected. A pronounced thought is separated from the link, that have been making it “living” (which means an extension of the mind, an ephemeral peninsula), and falls down to the external world, eventually becoming an object. Hence, it is easy to understand that sense of extraneousness we feel about what we have just said, immediately after that has been said. We perceive as illusory the possibility of deeply believing in that. We are tempted to believe that the only depth possible is meeting the other.

The so-called empathetic link, that joins an idea to an original matrix, is the same link, that ties the monument to an ideology and an ideology to that vital matrix itself. It is like if ideology was an extension of thought and it already contained in itself an autonomy will, that will unavoidably fall down into the world of objects. Therefore, the monument, even by showing its will to power, at the same time, claims to absence: the absence of the matrix that has constructed it in the very moment of its construction.

The monument summarizes in itself any a posteriori judgment.

About the ideological nature of sculpture, we wonder if isn’t rather ideology as actual as an object.

P: When we saw Mofo, the solemn and ambivalent sculpture that you presented last Spring at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in Bergamo, we have thought that it could be informed by the failure of a powerful intimate tension, that pushed towards the monument, blocked by a stronger, external, mean impossibility, coming from an historical-sociological matrix. Mofo has been gotten thicker prematurely within a destiny of perennial liquefaction. After all, Mofo is a monster withholding the evidence of a beauty that eventually became aching. Thinking of your work, but also of Thomas Houseago’s even though different in terms of media and modes, we would say after Goya that nowadays the sleep of politics, or at least of the res publica, produces monsters. What do you think about it?

A.F: We totally agree with your quotation from Goya. That is a recurring sentence among us.

Following your interpretation, we would like to reflect on the literal translation of res publica as “public thing”. It is interesting to notice how republic is by definition a “thing”, an object, first of all. The society as we mean it cannot stop producing objects; which is to reproduce itself. “Res Publica” seems to join two words, that are one the container of the other. It is like if the unit “thing” would be able to collect the multiplicity and hold it in itself by providing it with a body. A corporate monster, that takes us immediately to the famous movie of Carpenter, called, not by chance, “The Thing”.

P: We would define you “inductive sculptors”. Being carving an action performed on a hard matter, which implies the elimination of the superfluous in order to reveal the form , we have always assimilated the carving techniques to the deductive process that proceeds from a general principle to the particular instance. An absolute procedure, that does not allow any possibilities to the matter itself, seen as a mere material cause, physical opacity, prison of the soul, if you like extreme definitions. Vice versa, modeling techniques, performed on soft material, refers to an empirical method that starts from the particular instance to achieve form. Being form the purpose of the matter, the order to which matter tends per se, the sculptor becomes like a medium, a driver. Modeling techniques is related to a demiurgical sensitivity, that adds being where it lacks, and, by doing this, recognizes the dignity of the matter as that one of fleeting emotions. The word emotion has taken us immediately to Medardo Rosso. You made us think a little about sculpture and we feel more obsolete than we usually do. Is lost snow casting just a way to take to the paroxysm the matter’s free will and, in a sense, to play for high stakes at relieving your responsibility as a subject? What does Mofo have in common with your lost snow sculptures? Does Mofo perhaps represent the unconscious irreducibility of the subject/sculptor?

A.F: We would like to define our work by saying where we come from and, most of all, where are we now: into sculpture.

That means to be a little obsessed by it, for example by its history as a medium.

Also, this means that there is a technical knowledge, into which we dive every time we start a new project. It is something about techniques: from modeling to mold making, casting metal, etc. It is a wisdom that has been developed slowly, almost like an independent history. Actually, it could be said that the various civilizations succeeding each other referred to it only to direct its productive purposes.

For us, it is all about experiencing the technique physically, in order to review it within our limits through the visions that we are making up.

If you are into the sculpture then, you cannot see its outside. You just live there, like being inside a building which size is as unknown to you as its exact form. It is like in those thriller movies where point-of-view shot enable us to see through the eyes of the killer, but we not have any idea about how the killer’s/our face look like and we can just guess it. The form is revealed just when shooting perspective changes, in the very moment when you get out and are apart.

In many of our works, it is important such condition of blindness and the consequent disclosure of the form, given by the change of perspective. One observes the object extracted from it mold. And this applies to lost snow casting as well as to Mofo. In both cases, we pour some semiliquid material, wax or polyurethane, into an unstable mold. Later on we excavate the pieces, by unearthing them as they were archaeological findings.

We are interested in the course, in carrying experiences with us, which includes even to find figures. The goal of all our work is the aesthetic, the irreducible monster of the real for that we are seeking step by step, result after result.

Being us two working at the same sculpture, we conceive the bigger ones as a unit made of different parts. Almost a double self portrait.

P:Tell us about Scraper and about your performance works. Did movie

iconography strongly influences your “alien” way of altering body and space?

A.F: Scraper was made in 2011. We carry it out by working in a clay quarry.

The company taking care of clay extraction and bricks production had stopped its activity and the workers were laid off. All was motionless. Scrapers are the machineries used to collect the clay from the quarry. At that time, they looked like some colossi at rest (they are approximately five meters high, four meters wide and thirteen meters long). We decided then to take advantage of that non-activity period to coat one of the scrapers with some clay from the quarry.

It has been an intense work spread through that period. Such a state of suspension allowed us to focus on sculpture as simple modeling practice. We transfigured the volumes of the machine into its formal aberration. The surface was the only aspect about which we tackled each other and the quarry itself was an endless sequence of surfaces.

About our performative activity, we have always considered our physical presence, acting on the matter like some sort of visual interference for an hypothetical audience. In the end, for us the object is what matters and it is important to preserve its autonomy. In the case of Scraper, we have worked to make up an alien element able to inhabit underneath the skin of the landscape and to let its surrounding absorb it without consuming it. Movie iconography is very important for us because it redefines the sense of reality and of space.

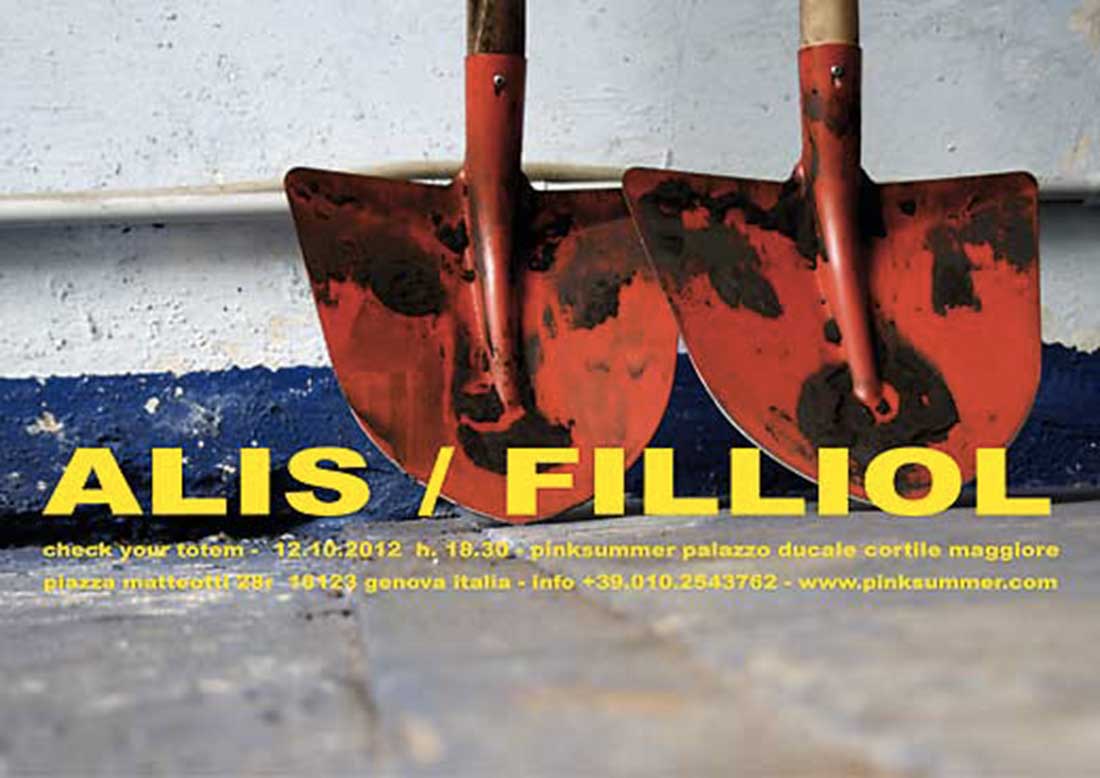

P: What are you going to present at pinksummer?

A.Fl: We know that Scraper will be there together with our new sculpture Mofocracy. We are currently considering the possibility of adding one more little sculpture.