Cesare Viel

Press-release

Cesar Viel (Torino 1964) presents at pinksummer an exhibition composed of two distinguished projects. “Diario contemporaneo” (contemporary journal), a work in progress featuring 41 drawings of the same format, in which the artist reproposes and edits various images taken from the omnivorous flow of national and international news reports, published on daily papers and magazines. Very rarely the drawings are presented by themselves as most of the times Viel accompany the images with a sentence handwritten in his calligraphy. Beside the theatre of the image, he adds that of the word, enhancing the relationship/clash between the two languages.

There where the image is presented as an objective fact, words intervene by marking the emotional path in which the image is meant to be channeled, they direct its reading, or, more in depth, its perception itself. Sometimes words are actual descriptive captions, other they are sentences drawn from Susan Sontag, Virginia Woolf, Peter Brook or Paul Auster. The handwriting evoke the diary, the subjectivity that rethinks the world and, willing or not, destructures and restructures it.

The message is clear, precise, without frills, simple and reflexive, somehow political. The twine between visual and verbal representation is a distinctive feature of Cesar Viel’s work and also connotes the other work presented by the artist at pinksummer for the first time. The sculpture called “Aladdin has been captured” is equipped with an audio track to evoke the eponymous performance presented at “Fuori Uso” in Pescara and later in Milan. During the performance, Viel, locked up for hours in a cage, was reading and writing down the tarots response to be given to the audience: therefore, captured, he entertained the audience and himself by playing the fortune teller.

Conversation with Cesar Viel

Pinksummer: The practice of associating images and words seems to be central in your work, moving from their incompatibility. Perhaps what we see cannot be told, not because words are inadequate to describe things, but simply because you know that words and things are not connected. The place of the language is not what eyes see, but what is defined by syntax. Language is a male principle, it is what distinguish the knowing process, it is not seeing, but interpreting. In “Diario” do you decompose and recompose the image according to the rules of a subjective taxonomy?

Cesar Viel: The disconnection between images and words, their movement on different layers and their mutual interaction are recurring distinctive features of my work. It is a destructuring and restructuring practice that intrigues me because it reveals a total productive division: the awareness of the disconnection between the two languages can generate the desire of a relationship between the parts with none of the two overwhelming the other and no destruction of diversities. It is when you realize that figures don’t add up that you start figuring out something. The work that I show in gallery, “Diario contemporaneo”, is first of all an infinite entertainment. It starts from October 2002 and arrives until January 2004, but it is actually an endless work: it will still continue across the time. So far there are 41 drawings on paper sharing the same format (29,7 x 42 cm.). The identical size of the drawings is the first rule that I have chosen in order to produce this “work in progress”. Then, the choice of black and white (only sometimes there is color, always red) and of a precise contour, neat, marked like that one of the writing paths. The chosen images derive from photographs published on daily paper, weeklies publications and magazines. Beside each image, there is the handwritten writing of one or more sentences acting as the captions published beside the photos on the newspapers pages do. Crucial for the development of this “Diario” is the structural relationship between image and sentence. On the printed paper, images “speak” to the reader through the given captions. The only apparently denoting purpose of the sentence indicates the way we should “read” the image. The published sentence affects the image, betrays it, twist it, justifies it, etc. My “Diario” aims to face this aspect of the everyday visual communication that submerges us. The mutual use and the abuse mutual abuse we make, and made to us, of the visual language and the verbal one. We cannot escape this structural “cage”, but we can try to play with it, to locate it in a different scene and to let it “speak” other voices and other tones. The sentences that I put beside or below the drawings belong, sometimes, to the category of “denoting” caption, other times they come from another category of discourse and they can be fragments of thought by authors such as Susan Sontag, Paul Auster, Virginia Woolf, Adolf Loos, Peter Brook. This way, the range of possible readings and observations of the images is made wider just by depriving the caption of its pretension of descriptive compatibility and by increasing to the level of “division” between text and image. At the same time, just because of that division though, eventually the image get closer to us in emotional terms. This is why the title “Diario contemporaneo” refers to a subjective element.

P: The generic ego typical of Sixties conceptual art, more focused on the process than the accomplished work, challenged the concept of authorship by dematerializing the work. Even by recovering that raw and tough rational stance, you and many other artists of your generation have brought the concept of author back and with it that one of emotionality.

C.V: From conceptual art I have inherited the awareness that no instrument we might use is innocent or neutral, being the result of a cultural construction, a linguistic process, that is eventually shown and revealed. At the same time, that purification, the conceptual dematerialization of the art, has finally produced the desire and the awareness of its contrary: the intervention on impure, cumbersome and not dismissible aspects of identity, of reality and of everybody’s emotionality. There are voices, feelings, conflicts and limits to the flexibility of bodies (as Foucault said). There is the impossibility of a complete of the vaporization of the ego, the unavoidable and strong relationship between me and you, the attraction of the dialogue between the individuals. In my generation, all this has produced the tendency to face an art capable of multiple views, personal and complex, anonymous and characterized at the same time. A view holding together the drift and the concentration of the ego. A subjectivity not strictly meant in autobiographic terms, not devoted to be removed by a supposed “neutral” practice, but that is able to consider its position and the conditions of its existence. To me, same assumptions apply to the practice of the performance too.

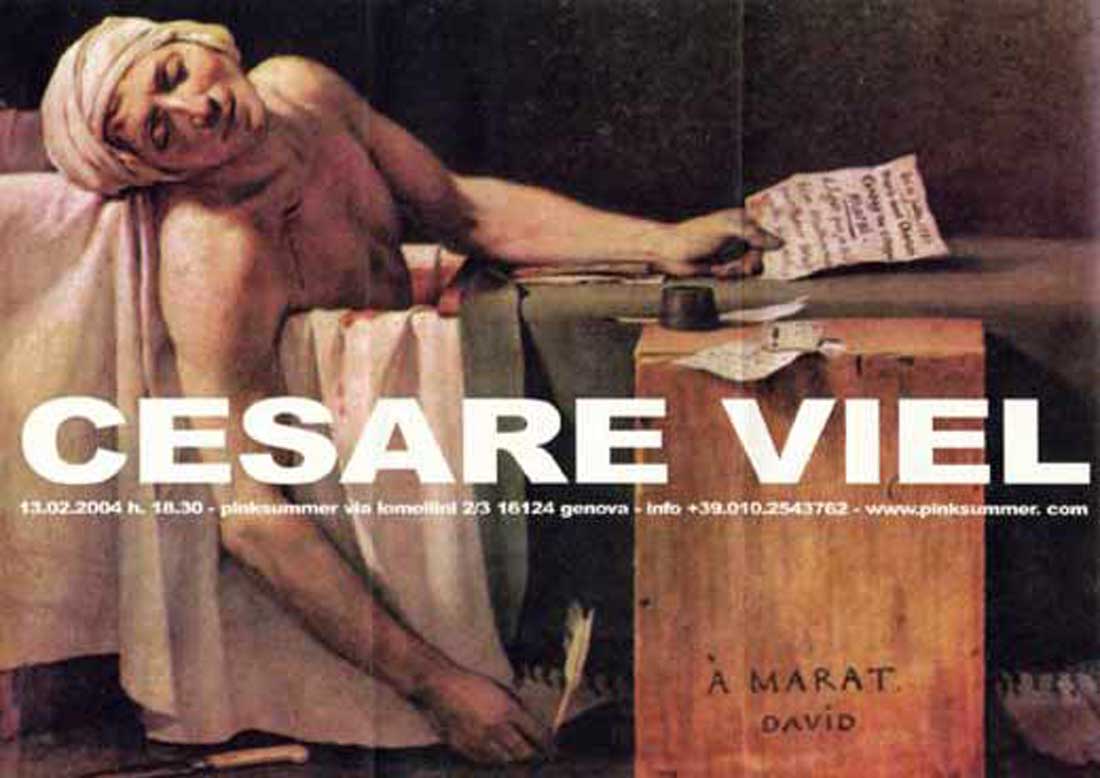

P: For the exhibition invitation you chose the image of David’s Death of Marat. The art historian Carlo Giulio Argan claims that in the case of David, neoclassicism assumes an ethical stance rather than a poetical one. They say that David often went to visit the condemned while they were taken to the guillotine and he portrayed them with a few lines of extreme intensity. Among those portraits the only left is the one by Maria Antonietta. Talk about this choice, please.

C.V: First of all I have chosen this image because I like it very much. It comes from the revolution: a moment when opposite elements mingle and cross each other, life and death, enthusiasm and desperation, happiness and pain. I did not choose it because some nostalgic formalistic desire or a mere provocative stance, but for the possible twines with my works: the complex relationship with contemporary social events (after all David has been the first political artist-reporter of modernity); its clear awareness of the staged relationship between theatre, image and writing (Marat still holds a letter in his left hand and a pen in his right hand, the ink pot and another letter are clearly visible on the wooden basement showing the dedication and the signature, two names, the of the portrayed and that of the author); the relationship between the violence of the crime, of the fact, and the rigor of the drawing; the presence of a political body and the dry mode of the composed language adopted to show it. To me, all this provokes a profound mental emotion and it is very contemporary, even though the painting is abysmally far away in time. To be more precise, 211 years are gone since such a secular and “contemporary” work was painted. Also, it is true, I am interested in dealing with the ethical aspect of our relationship with the visible, even though do not like to declare it For me ethics has to be above all an emotion, a consequence of behavior, not a program.

P: The drawings you will present at pinksummer seem to us some sort trompe-l’oeil, as a matter of fact are organized around an object, the report, but such an object is organized around to your gaze. Nancy asserts that to paint, to draw, is to exit yourself, from the eye exit the gaze, the eye’s view, and it its because of it that the subject becomes subject. The portrait is the endless expansion of the one, it is not by chance that this project potentially endless is called diary, isn’t diary a literary self-portrait?

C.V: I move from the report of the present time to obtain a possible contemporary iconography, by forcing the images to tell something else and the form of diary allows me to avoid the production of any hierarchy of values or contents. The horizontal and public criterion of such a diary project actually ends up in a denial of the idea of diary as private self-portrait. So, if a self-portrait emerges, I am not aware of it, and that is perhaps an anonymous and pluralistic self-portrait.

P: Again Nancy asserts that portrait exists in absentia, meaning that it is made in order to conserve the presence, it is built on the idea of likeness and ricognizability, which differs from idea of the copy or reproduction in terms of approximation ratio. While evoking, the portrait makes immortal, which means escape death. Why did you feel the need of taking out of the flow these facts, to present them ins the same décor, independently from value and matter?

C.V: Initially I felt the desire to draw these images, these news, in order to transform them, to take them out of something, I do not know if to save them from death (this is already an ethical goal and I do not feel like to declare it). Anyway, it is clear that setting them up as pages from a dismembered diary, they stand apart the information flow to find themselves in a context that makes them still recognizable but different, fragmented and most of all fragile, because necessarely devoted to a careless use. All the images turn out to be what they are: means used for whichever aim, capable to mean anything according to the most various intentions. This is their extraordinary power and “tenderness”. This project of mine is endless because I think that endless is the subjective desire to give a context to the reproduced images surrounding us every day.

P: Beside “Diario” you will present at pinksummer a sculpture, that reminds of a performance in which you were reading tarots in a cage and playing the fortune teller. A representation of the representation. Tell us about this sculpture and the performance and also tell us more about the performance as a practice, an exercise within your work.

C.V: The sculpture “Aladino è stato catturato” has the same title of the performance from which has sprung as an ironic and uncanny double. During the performance (presented for the first time in 2000 at “Fuori Uso” in Pescara, later presented again in April 2003 on the occasion of the first public event organized and promoted by the Associazione Ida, Isola dell’Arte, to which I participate in defense of the building Stecca in Milan, risking demolition because of a very questionable urbanistic project) I was sitting in a wooden crate-cage for several hours, reading and interpreting tarots and recording on paper those unlikely and awkward sentenced told by cards. The fairytale-like topic (Aladdin, the magical lamp, the flying carpet) was a pretext to face ironically the condition of a subject who, finding himself literally caged, has momentarily lost his own force and, to kill time, try to find a possible solution in the contradictory responses given by the cards. The action of reading and the psychic writing, the presence of a body exposed to the gaze of others, the presence of the others around the cage and the perceptive destabilization due to the apparent normality of my condition of captive, were the elements at stake in this performance. However, I felt very soon that the energy sprung from that action did not mean to stop with the end of the performance, there was an obstinate part that did not accept to be “locked up” and resolved in the dimension of the performance, hence the need of making a sculpture: an independent work. Now this performance has found its positioning and definitive form. As I have pointed out in a previous answer, for me the practice of performance is important just because it allows to face in its concrete reality the delicate aspect of the spatial and relational quality of a subject. Synthetically I can say that inside of my work the practice of performance is a fundamental moment to test languages and issues related to the exposure of subjectivity and identity among other human presences. It is a matter of public sharing an intensely emotional moment that becomes political too, in the widest sense of the term.

P: Angela Vettese in an article published on Il Sole 24 Ore in 1998 told about “misfortune” of the young Italian artists asserting that even the most promising among the young ones perish in absence of the deserved acknowledgment. According to the author, the causes can be determined by the Italian financial position, too poor compared to rich countries, too rich compared to the poor ones; for the lacking structures “and even though present, ruled by small local egotism and normal ignorance”; but, most of all, she connected the issue to the prevailing love of formalism, that by making Italian fashion and design great, has never helped the Italian artists: “seen from abroad, the goal of making up a form out of a thought appears often a sign of low attention to the content”. Finally in that article, she asserted that in Italy” the “old artists”, afraid of losing their position, block the road to their students”. You teach at the fine arts academy in Genoa, what is your position in front of your students?

C.V: It is true, in Italy the general condition of attention for contemporary art are not good, even though during the last few years something has changed positively. When I began to exhibit in the end of the Eighties the void and the indifference were making the situation heavier than now. The presence of the old masters was more tangible, the few museums seemed impregnable fortresses and the public institutions were completely soaked in a self-conservative management. Since some years ago I teach at the Academy and I entertain a very positive relationship with colleagues and students. Obviously I do not consider myself a “master”, it would be hilarious to me. I try to stimulate as much as most possible the curiosity of my students and the free and dynamic spirit of research, I do not give a priori recipes and I do not mean to set myself as a model (I never speak of my artistic practice and I hate narcissism). It is very interesting, whenever you feel that you have contributed to give birth to questions and to open a door or a small opening. That is the point when you too learn something from them and discover the beauty of finding yourself among active subjects. Culture and teaching are phenomena of life with strong roots in the experience and in the emotional and intellectual quality of experience. I believe that this is the more important aspect of the relationship of transmission of the knowledge.

P: We remember a work by Boetti of the late Eighties, drawings obtained simply by tracing the covers of news magazine from a certain and limited period of time. Panorama, L’Espresso, L’Europeo. Pencil on white paper. Do you know this work? Is there any connection with your diary?

C.V: I know and appreciate Boetti’s work and I consider him one of the most interesting Italian artists of the second half of the 20th century. Some years ago, I carried out a photographic work that was an explicit homage to his “Gemelli” of 1968 too. In this case though, my work (“Diario contemporaneo”) is barely connected to his. I would rather speak about a family resemblance (to say it after Wittgenstein), meaning that eventually any art work recalls always at least another one, and this is a beautiful thing that happens. “Diario contemporaneo” though, is not a work on objective tracing of the covers of popular magazines of a clearly limited period (Boetti chose October 1983), but it is a selected and partial editing that generates a shift, sometimes very clear too, dividing the photographs from their reading. The process is not based on the mechanism of serial objective recording, but on the spoiled and conflicted reassembling of images and verbal language added. It is a subjective process of recontextualisation, maybe closer to the situationist attitude, always speaking about evocative sense of another family resemblance. I meant to manipulate images that are in front of our eyes every day, just because, having them every day in front of our eyes, we tend to not see them as a problem anymore.