Tomas Saraceno – On Air

Press-release

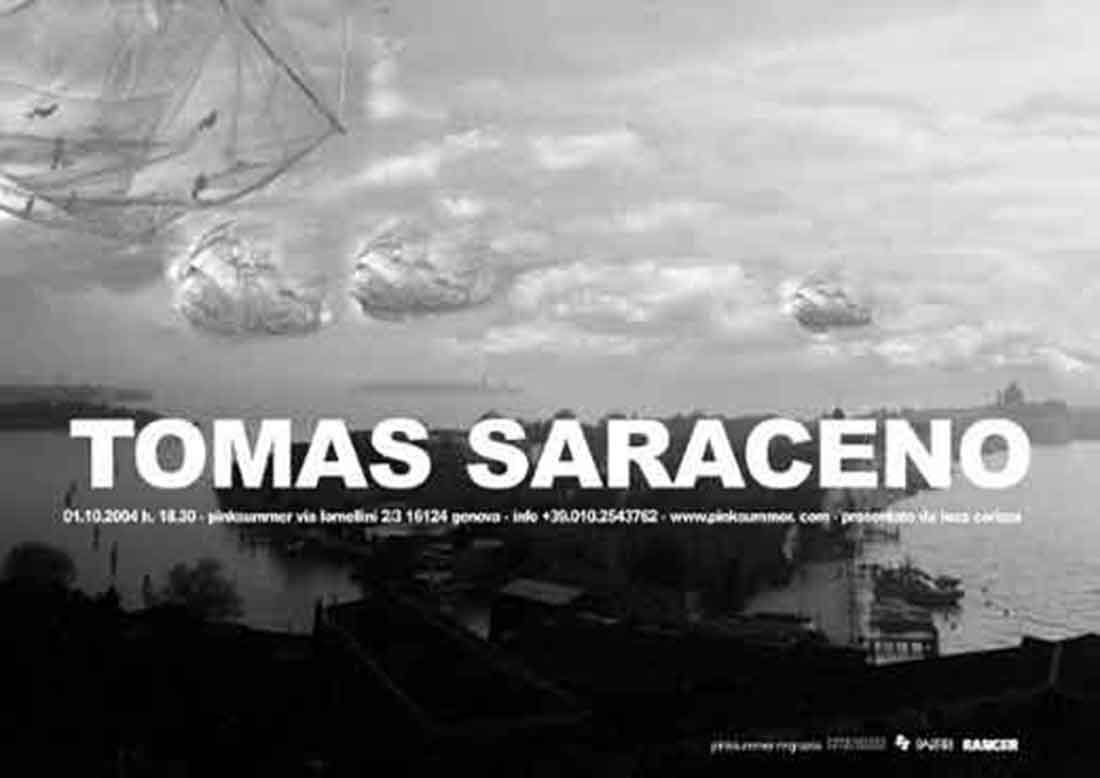

Pinksummer presents Tomas Saraceno, invited by Luca Cerizza

Conversation with Tomas Saraceno, Luca Cerizza and pinksummer

Note:

the interview, from a press release, has spread widely and we think that it could offer interesting hints regarding the approach to the artist’s work as well as regarding the relationship between art, architecture and the politics and social connections, so we decided to leave it whole.

Pinksummer: Superstudio in 1970 wrote “In those years it was becoming very clear that continuing to draw furniture, objects and similar domestic decorations was no longer the solution to the question of living? And it could help even less to save it’s own soul”. “Radical” architecture of groups such as Superstudio, Archizoom and other collectives started in the second half of the 60’s to free itself from the pragmatism of the discipline to project a philosophy of life. In 1973 again Superstudio declared: “Architecture never touches the big issues, the essential topics of our lives. Architecture stays at the corner of our lives and takes part only at a certain point of the process, usually when the action has been codified?. You are an architect that works as an artist or an artist with a background as an architect: do you think that art, with its finality tout court, if we can call it finality, is to inform ideas, is more adapt to investigate the big issue of life or even only to de-futurize the future?

Tomas Saraceno: Usually I try to leave the task of categorising my work to the others. First of all we should define the work of the artist and of the architect in history. For me it is more interesting to find interdisciplinary events between those two areas of research. Up until now I felt more opportunity with art than with architecture: with art the possibility of expanding the process of perception sets a critical attitude into motion that considers and reconsiders, re-interprets, decodes your position reverses the reality, reverses the world. If I decide to look at this keyboard for four hours without touching it, my relationship with it will not be the same. In any case we can apply the term “architecture” to an infinitude of contexts and understand that architecture could be a thing much more vast: architecture of computers, architecture of a poem? Architecture is everywhere and cannot be viewed essentially as the science of constructing houses, cities, etc. I think that the aims and interactions between disciplines must be continuously re-invented for each specific context. After operating a dissolution of ?disciplines?, We have to try to activate a process of re-actualization in relation to ever changing contexts, to therefore find a feedback for a faster process of communication, capable of imagining more elastic and dynamic rules. Maybe we can learn from the principle of ecology as a system of cohabitation of different cultural areas. This would help us to understand the need for a principle of cooperation. It is a system based on an entity-principle of “networks” (all the living systems communicate between themselves and share areas of research) “cycles” (all the living organisms are fed with a continuous flux of substances and energy from their environment in order to survive and all those organisms produce a surplus that becomes usable for other species. In this way the substance is always in circulation through this network of life), “partnership” (the exchange of energy and resources in an eco-system is supported by a pervasive cooperation. Life on the planet is supported by the principles of cooperation, partnership and networking), “diversity” (an ecosystem gains the stability through the richness and complexity of its own ecologic network. The bigger the biodiversity the bigger the resistance), “dynamic balance” (an ecosystem is flexible, is a network in continuous flux. Its flexibility is the consequence of multiple feedbacks that keep the system in a status of dynamic balance. Not a single variable is maximized, all the variables are floating around their optimal values). It would be interesting to obtain this kind of system of relations among art, architecture and science.

P: In Greek “utopia” means no place, it is the name given by Tommaso Moro to an island governed by ideal political, social and religious structures. Utopia is the projection of a better world that is the opposite to the reality of existing history. Utopia draws strength from a rationalization that opposes the madness of current times. In your work this concept of Utopia is present, making use of highly technological materials as well as a sense of wonder. Your utopia seems to be one of building habitable unity, urban agglomeration, and cities with a feeling of the extraordinary. Your Utopia seems to be one following the movement of the clouds, allowing you to surpass national boundaries, a bit like that happening in airports. These units are contained in balls made from a material patented for this use (aerogel). Do you think that Utopia is something that can be realized or is it an unstable concept, that creaks when confronted with reality?

T.S: Utopia exists until it is created. A hundred years ago was it not considered to be a utopian thought that people could travel by aeroplane? Now, five hundred million people fly every year. In 2010 it will be three-trillion. The idea of utopia is in constant mutation and changes according to the era. I think that the individualism that characterizes this period in history makes this concept an unstable and fragile one. Now there is an ever better consciousness of sustainability in our lives on planet earth. In this way, my work tries to explore and interpret the present reality, using technological innovations for new social objectives. For example, my idea of Air Port City is that of creating platforms, habitable cells or cities that float in the air, that change form and join into each other like clouds. This flexibility of movement, in relation to the national states, finds an answer in the organized structures of airports: the first international city. Airports are found in various cities and are divided by “air-side” and “land-side”; with “air-side” you are under international law. Every action you make will be judged according to international norms. Total control under freedom. Air Port City is like a flying airport; you will be able to legally travel across the world, taking advantage of the airport regulations. Work on this structure tries to contest political, social, cultural and military restrictions that are accepted today, in an effort to re-establish new concepts of synergy. A year ago, with the help of engineers and lawyers, I took advantage of an application of a new material called Aerogel, to be used in vehicles that are lighter than air. These vehicles use a gas that is lighter than air to rise up: helium, hydrogen, hot air, a mix of these, or others. The use of Aerogel gives these vehicles the possibility of flying solely on solar energy. These vehicles are the more efficient alternatives for our future of mobility and for a possible “colonization” of the sky. There will be no more need for airports, air pollution will cease; they will be efficient alternatives for new satellites and will create new possibilities for communication. These situations will makes faster and more energetically-sustainable movements possible, an incredible mobility for people, information, data, creating a continuous re-definition of the boundaries and of national, cultural and racial identities. Everything will move with greater ease, creating continuous and quicker relations and inter-relations, and the possibility of choosing conditions of life and preferred climates. They will be like entities in a permanent state of transformation, similar to nomadic cities. Gypsies will never go back to the same place, simply because the place will continuously change. Air Port City is like a huge synthetic structure that works towards a real economic transformation. Obviously the Air Port Cities would agree to development without damaging the biosphere, in this way improving the conditions of life on earth and avoiding any existing dangers and menaces, such as a possible meteorite collision, urban over-population etc. Moving from a personal “belief” to a collective one is the first step towards the realization of this idea. After the unification of Europe a “europeanafroamericanasianoceaniasfydsdf” will be created: like the continental drifts at the beginning of the world, the new cities will search for their positions in the air, to then find themselves in the universe. From Cirrocumulus to Cirrocumuluscity!

Imagine: around the world without a passport! It would be important to reach a new international agreement that would allow citizens more than just a passport, and for citizens without a state to have a “united Nations” passport, which would give them basic human rights in the countries in which they were staying permanently or temporarily, as Majid Tehranian supports in “Worlds on the Move”. Moreover, as Yonathan Friedman notes, at the moment only 2% of the world population migrates. My idea of cities and civilizations encourages a continuous mobility. If, as maintains Lewis Mumford, cities had origins in necropolises and therefore from a culture of the dead, today we have internet sites that put the ashes of the dead into orbit, with the motto “Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Stardust”! History seems to be repeating itself: we are ready for flying cities!

P: Once Buckmister Fuller said: “The spaceship Earth was so extraordinarily well invented and planned, according to our consciousness, that the humans were on board for 2 million years without even suspecting that they were on board a ship”. Newton maintained that gravity is the force of the darkness, the cause that regulates the cosmos. The search for transparency and lightness in your work seems to oppose the law that chains corporeality: is flight an ancient metaphor for liberty? Isn’t the sky a reality beyond the place that imprisons?

T.S: Revolution! Think about the fact that the invention of the hot air and hydrogen balloon came about as a means of escape and protection, around 1780, in the time of the French Revolution. It is significant that during these times of uncertainty, the people looked to the sky to escape from the reality of earth. The balloon created a great way to level out the inequality of French society. The aristocracy could have large areas of land, but the sky was free and belonged to everybody. And in this way, further on in history, when a society goes through a traumatic phase, people look for refuge in the sky to escape from the chaos and uncertainty. Brian Charlesworth wrote: “As we emphasized several times already, natural selection cannot foresee the future, and merely accumulates variants that are favourable under prevailing conditions. Increased complexity may often provide better functioning, as in the case of eyes, and we then will be selected for. If the function is no longer relevant to fitness, it is not surprising that the structure concerned will degenerate.”

P: What will you present at pinksummer?

T.S: In-form the air: Air under different pressure? Two entrances into the gallery will take you under two different “pressures” of air. If you go up the stairs you will end up inside the gallery: here the “pressure” is higher but not high enough to make your ears pop (air pop). Taking the lift however, another staircase will then take you to the roof of a new room inside the same environment as the gallery, with a minor pressure. A transparent PVC membrane 6 millimeters thick and 6 metres high will let the gallery breath, keeping you suspended in the air. Your shadow like a fresco projected onto the ceiling. “Pneu”: base of all of nature. “Pneuma”: air. “Pneumatos”: to breath. “Pneo”: to live-to reside in. It will be like a living organism, a space that reacts and “behaves”. A section of an Air Port City, flying. 513 m3 of breath will raise you up, will release you from the earth and bind you to the others. A new medium of space: like everything, architecture has to mediate between an exterior and an interior context, the earth mediates and protects from the exterior space of the atmosphere, but it is in a permanent state of instability. Two pressures, the same air: Genoa and Mediterranean. A sign in the European-cushion. If you share a same volume of air, a hermetic space, you will make the air so solid as to cause suffocation. The entry and exit of people into the inferior space will allow therefore, the change of air. The mass of people suspended will determine the intensity of this exchange. As happens with the wind, local or global, produced by pockets of air that move around, in an attempt to equalize the temperature and difference in pressure. Marx wrote: “all that was solid had melted into air”.

Luca Cerizza: A phrase from a recent song by Blonde Redhead springs to mind: “Behind these clouds, I am almost home…”.

P: In the first presentation print of Genoa 2003, European capital of culture, with regard to its exhibition “Arts and Architecture”, Germano Celant affirmed that at this moment in history, architecture is more fashionable than fashion. We believe that fashion and fashions are born from a necessity and, in fact, for a few years now there has been a lot of attention paid to architecture and also the world of art strongly shows this interest. Architecture as a whole is like an intellectual projection that leans towards a better world. Each architecture strives to be a place to live and to act well. Do you think that this interest in architecture is a tangible manifestation of the fact that we have left ourselves on the shoulders of the 80’s and 90’s, noted for their individualism, firstly euphoric and then depressed, to enter into a phase of task, true and apparent, from a political and social point of view?

L.C: Above all we have to ask ourselves what we mean by “architecture”. Today it seems to me to be a term more elastic and complex than ever, that doesn’t necessarily only mean large buildings that are more or less institutionalized and “fixed”. Architecture can be a holiday camp, a prison camp, a military base, network space, an outfit. Whatever is meant by it, it seems to me that, on the binominal art-architecture, different needs and urgencies converge. In one way, since a few years ago, we have been contributing to an ever more detailed hybridization of contemporary art with other languages, in a continuous dialogue with all spheres of creativity and knowledge. Architecture and town planning is amongst these. A deeper relationship and comparison between artists, town-planners and thinkers is being sought, a communal territory of exchange and reflection, without “caste” divisions. Of course, there is a renewed task for artists, critics, theorists, and administrators of analysis and politico-social polemics and the consequent attempt to think of alternative solutions to the problems of building and living, in the broader sense of the words. And so, a renewed attention for the formalities of everyday living on all levels, with lack of balance and transformations, mass migrations, extraordinary urbanization, demographic problems, the huge surrounding rush, the impact of new technology on architectural tasks and on our way of life, on the symbolic and political effect of architecture. Art and architecture also meet each other in the museum: the said “Bilbao effect”, immersed following the construction of the Frank Gehry museum and the consequent “massification” of the fruition of contemporary art, has renewed the debate on the symbolic and ideological effect of the museum institutions. Then, at a process that had already started, there was September 11th. The closing event of the 20th century, the image that has glued itself with more strength onto the collective memory of the world, is linked to the dramatic destruction of a building, which was one of the symbols of the West, for the functions it held and for what it represented both visibly and culturally. In all, I believe it to be something more than a passing trend, even if this danger clearly exists. But the exhibition stops in the year 2000, and probably surrounds the debate on this and other emergencies linked to architecture and town-planning. As far as I’m concerned it has always been of interest to the poetics and the problems of space, understood in a far greater way, to have myself thrust towards working on these hybridizations and relations. Even those that I did with electronic music went in this direction. Obviously the fact that I transferred to Berlin in 2000 had a strong influence, both for its identity and the history of the city and for its cultural and artistic atmosphere.

P: In Italy “young curators”, and even more so “young artists”, tend to remain “young” forever: it hardly ever happens that they are called, to put at disposition the fresh knowledge of the militancy, of a “old curator”, clearly more reassuring with regards to political investments and to collaborating with a grand show with grand budget. At the same time that pinksummer will be showing Thomas Saraceno’s, whom you invited, Celant’s colossal “Art and Architecture” will be opened in Genoa. We are pleased that our city has finally invested in the contemporary and that the exhibition is led by a professional who will be a guarantee of quality, but we would like to know on what basis you would have worked for a section of the show that is not yet historicized.

L.C: To be honest, I don’t really know much about the show and it’s difficult to talk about it without having yet seen it. From the information that I’ve had I can imagine, and maybe it couldn’t be any other way, a show of a “generalist” character and with a lot of historical and spectacular breath, instead of being strictly about news and/or militant. Concentrated, rather, on the power of seduction, maybe a little bit “Hollywood”, on the architectural imagination and on its big names. From what can be foreseen from the list of the youngest artists invited, who are however all of high quality, I can say that I would have stretched the list to characters more interested in social, political and town-planning dynamics for wider breadth, rather than to the relationship with the symbolic and architectural form of the building. The list would be endless, but I will say that I would have paid more attention to the “macro” than to the “micros” dynamic, to the town-planners more than to the forms of the architecture, even by analysis of the contexts and specific and local situations. For example, it would have been interesting to present research on the “alternative” social community, on the urban developments of the contemporary megalopolis, on today tensions linked to globalization, to confines, to cultural identity, to atmospheric problems, to ecological tenability, and of course across a less precisely western point of view. An attention to marginal, non-official, hybrid, precarious, improvised and nomadic architecture for example. If we then stopped at the relationship with the building, it would have seemed interesting to me to reflect on the impact of new technologies on architecture, towards the creation of an ever more flexible, dynamic and continuously re-defined atmosphere, where the traditional spatial-temporal categories are placed into critical situations. Or, on the ever more urgent questions linked to the relationship between public and private spaces, relative to the social problems, to consumption and entertainment, for example. In short, on the one hand an analysis more decisively “on camp”, and on the other a vision of the future, maybe linking expressly to the important and stimulating stage of architectural research that the same Germano Celant defined as “radical” so long ago. In this sense, there are many examples of research carried out by international artists (Tomas Saraceno is amongst these) and by other good Italian artists who take up and actualize the introductory ideas of these years, confronting them with new demands. But it is a story from which more foreign art and architecture has been appropriated (I’m thinking of Holland and France for example) than Italian. “Bringing it all back home” would be interesting, as Dylan would say. Also it seems to be very difficult to forget that in Genoa, in the very recent past, whilst the citizenship was invited to systemize the flower pots with care, it turned out to be one of the most worrying and violent episodes of “militarization” of the urban web, during the days of G8. A moment of great symbolic force of the tensions between different social and political visions of today, on the real ground of the city and of a city so morphologically particular as Genoa. I would say that from Genoa itself we could start an analysis of these problems that have been, once again, subject of debates, more abroad than in Italy. But it’s to be expected to say that this would create more of an embarrassment to he who sponsored this manifestation.

P: Tell us how you met Tomas Saraceno, what was the first work that you saw and what intrigues you about it?

L.C: I think I heard him and his work being talked about by shared friends at the Städelschule of Frankfurt, where Tomas had studied in Peter Cook’s class who was one of the founders of Archigram and is still an extremely active publicist and architect. Maybe the first time I met him was at the Tate London, at Olafur Eliasson’s show, who I worked for a few months and collaborated with on a few projects. Then he took part in a collective in Berlin and I tried to get in contact with him. We began to communicate via email and then, when he passed through Berlin a few months ago, I met him and we spoke at length. I would say that it was, above all, the thought and research of Tomas that interested me, rather than a single work of his. His seems to me, to agree with Yona Friedman, to be a “realizable utopia”. What fascinates me is the strength, courage and honesty of his vision that touches some themes and interests that I have worked on with a certain continuity over the past few years: the poetics of space, social dynamics, ecological sensitivity, and imaginations of a possible future between architecture, science and politics. I’m interested in his link with some of the research on the so-called “radical” stage of architecture, in the direction of social forms and future aggregation. I think that Tomas is a generous and optimistic artist, but at the same time not ingenuous, with a critical but strongly constructive attitude. And I like that. I’m convinced that this kind of tension is almost as urgent in this historical phase as irrationality and violence seems which render thoughts of new and better forms of civil communities and societies impossible.

The installation will be visible until January 10, 2005