Georgina Starr

Press-release

Pinksummer: “Freud holds that there is a very strong link between artistic creation and childhood, childhood as a mix of memory and repression and he associates the idea of childhood with that of death: childhood memories are often inhabited by the dead. In many of your works the idea of childhood is central, we are thinking of “Party”, one of works we most love, in which, you told us of being inspired, regarding the preparation of foods and decorations, by the birthday parties that your parents organized for you when you were a child, but also for the “Bunny Lake” saga you start from the end of the movie/thriller of Premiger, thinking : Bunny Lake has been saved, but what kind of teenager will she be? What does childhood represents for you, in your works?”

Georgina Starr: “I am interested in the fact that childhood can only exist in a fictional way because we only have it as a memory, it will never be how it really was again. This is something that I’ve touched upon in many works, but especially the Bunny Lake series. My whole memory of the film was from seeing it when I was a child. This memory uncovered a much more personal story of what was going on around that time in real life. My relationship and memory of my sister became a kind of parallel to what was happening in the movie.

The idea of missing children, abduction and revenge were all subjects that were close to me as well as subjects that are dealt with in the fictional film. Both ‘Bunny Lake’ and ‘Targets’ deal with a person who is angry about something that happened in the past and feels a need to reek havoc by taking revenge. I saw parallels with my sister who was ‘saved’ from being abandoned and Bunny who was also ‘saved’ at the end of the film. And that’s why I ask in my text in The Bunny Lakes book, “Could we save her? We all tried. Deep down, I think she didn’t want to be saved at all”. Just because Bunny was safe it doesn’t mean that the trauma won’t affect her. In the same way my sister was safe with us, but this wasn’t enough.”

P: At your nice party, in all cases, nobody came, the expectations of happiness have been frustrated and it became something of very very sad, and the essence of Bunny Lakes is epitomized by the pink, fatty characters, reminiscent of the seventies, on black background of the cover of the white vinyl record that is the soundtrack of the project. The dripping of the pink letters is very sinister. Both in Party and Bunny Lake there is a strong pessimism: do time and reality sweep away the illusions of happiness and life?

G.S: I think all my works have a dark sinister side, however happy and colourful they may look from the outside. In the fiction of The Party, the woman is seen to be having a really fantastic time alone. However we know from reality that having a party with no guests is actually a sad and depressing experience and that no amount of glitter and colour can change that. But the piece is more complex than that, because as well as it existing as a video (a fiction), it was actually me having the party, which I did in reality for 3 days alone. So it works on many levels.

P: when we came to London to see Bunny Lake Drive In installed in a old factory, we noticed, more than when you presented Bunny Lake Collection at pinksummer and at the Venice Biennale, that your work could be interpreted like a sort of metaphor of memory, we are thinking of the whole of the show, so precise, but in particular of the pierced screen, in whose back you projected parts of the movies Bunny Lake is Missing and Target, that have to be considered primary materials, which you colonialzed and re-invented to create a new story.

G.S: Anthropology has always been studying this negotiation between individual imagery and collective images. What does cinema represent for you?

P: I have always been fascinated by the power of the filmic image. As a child growing up my mother was obsessed with movies from the 40’s and 50’s. We would watch the films together and sometimes I would prefer to live through these film than in any real life situations.

As a child there was always a blur between fiction and reality. I was much more taken in and affected by films then. I have a very strong memory of certain films that I watched, and these merge together with what was going on in real life when I saw the films. In my work from 1995 Visit to a Small Planet I rewrote the script for the original film from memory, but I included what was going on in my own life when I watched the film aged 10. I re-enacted moments from the film and from real.

In the Bunny Lake work instead of re-enacting I followed on from the what happened in the movie and took it further, imagining what certain characters would do next and interpreting their next moves to create a new work.

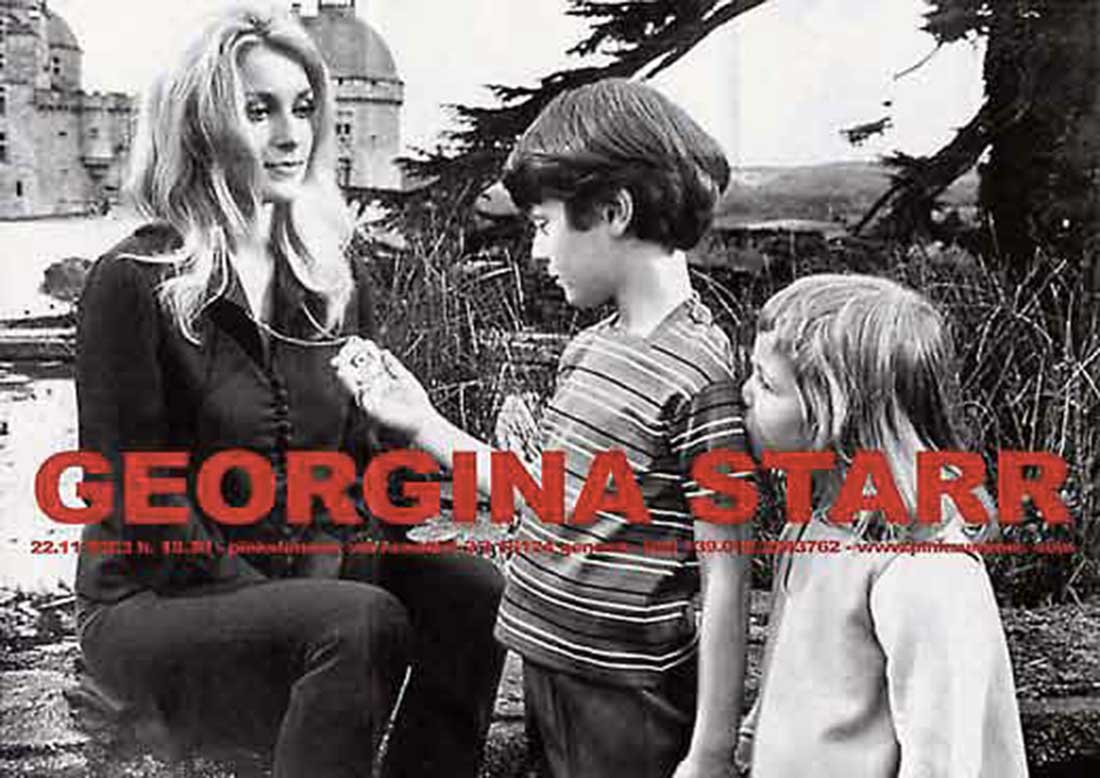

P: We know that you recently met the actress that in ’65 interpreted the missing and saved child, Bunny Lake, the same young actress that together Sharon Tate, the murdered pregnant wife of Polansky, is in the image you choose for the invitation card of pinksummer show . What did she tell you? What does she remember? Why do you wanted to meet her? How many other movies she did?

G:S: Yes I met Suky Appleby the actress who played Bunny Lake. It was always in the back of my mind that I would like to meet her. I knew that she only ever played in the two movies “Bunny Lake is Missing’ and ‘Eye of the Devil’ so it would be hard to track her down as she was only 5 year old and the films were made. This year I started to work on a synopsis for a film script and I had been thinking a lot about the actress and who or how she was now. I’d spent the whole summer writing (fiction) about her and when I got home I decided it was time to try find her. Through a series of weird coincidences I was able to write to her, still not knowing if it was actually her. But it was. We met last month and spent 5 hours together.

She talked very openly about her experiences on the two films. She told me everything in great detail and could describe the sets and the other actors and directors as if it was yesterday. For various reasons I can’t go into too much detail about all this right now, it was all very personal to her and she was deeply affected by her experiences. What I found very interesting was the parallels between my fictional Bunny Lake and the real ‘Bunny Lake’, and there were some fascinating and strange crossovers. My new script is still being developed and I hope to use my fictional version of her character as a starting point for this new narrative.

The second film that ‘Bunny’ was in was the first feature film that Sharon Tate made in 1966. The film was released with a documentary about Tate (All Eyes on Sharon Tate) and highlighted that she was a new and up and coming star to watch. Sharon Tate never really had the time to let her light shine as she was murdered in 1969 aged 26.

P: Your project are tales, sometime are many parts that shape a tale, every work is a fragment of a tale, a clue, a phrase underlined in your imagery. Telling stories means to be here and now, but at the same time to be far away in another time and space. What does it mean for you? When do you feel that a story is finished?

G.S: I suppose the story could go on forever but sometimes you just instinctively know its time to end. I have worked on the Bunny Lake theme now for over 4 years, I never thought it would go on so long. Usually my pieces take a year or less to make. It’s more about how much interest I can sustain in the subject. I’ve said before that I can get bored easily, but in this case I didn’t, there was always a new part to explore. I knew it was coming to an end when I re-constructed the garden in Rome. Bunny had come full circle, from the first time I saw her in the garden in the Preminger film, to her introduction into my work in the video and photos in The Bunny Lakes are Coming, she transformed again in The Bunny Lake Collection and Bunny Lake Drive-In, and now she was back inside the garden.

P: What will you show at pinksummer?

For this last episode in the Bunny Lake series I will show a new video installation, Inside Bunny Lake Garden. The piece began at the Villa Medici in Rome where I re-constructed the garden from the last scene in the Otto Preminger movie. This garden, complete with an impenetrable brick wall and child size grave, was used to film the video for Inside Bunny Lake Garden. I will show a two-screen video projection which simultaneously follows the action in the final sequence of the real movie (Bunny Lake is Missing), alongside the movements of a young Bunny Lake look-a-like imprisoned in the re-constructed garden. There are subtitles on the video which narrate a text I wrote and was published in the recent book The Bunny Lakes. The text shows that the Bunny Lake theme not only took its references from the two 1960’s films, but also from a more personal real life history. The garden in Rome no longer exists so I have had a scale model made which I will also show. It is identical to the original and was also used to film parts of the video work.